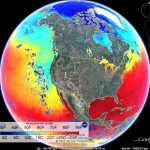

The simplest definition of salinity is how salty the ocean is. Easy enough, right? Why is this basic property of the ocean so important to oceanographers? Well, along with the temperature of the water, the salinity determines how dense it is. The density of the water factors into how it circulates and mixes…or doesn’t mix. Mixing distributes nutrients allowing phytoplankton (and the rest of the food web) to thrive. Globally, salinity affects ocean circulation and can help us understand the planet’s water cycle. Global ocean circulation distributes heat around the planet which affects the climate. Climate change is important to oceanographers; therefore, salinity is important to oceanographers.

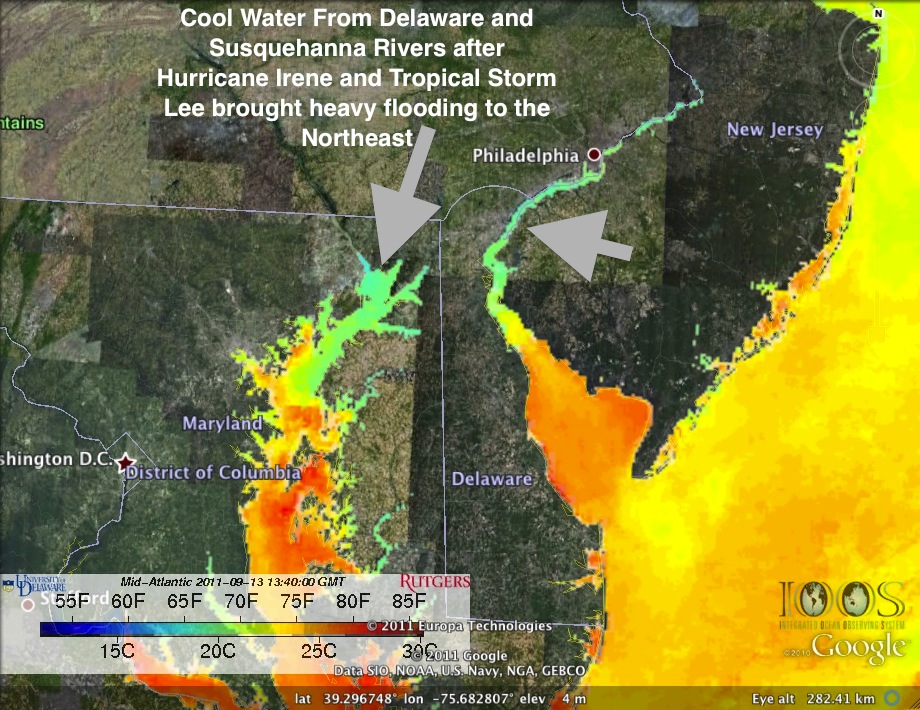

Salinity doesn’t vary that much in the open ocean, but it has a wide range in the coastal ocean. The coast is where fresh water from rivers and salt water in the ocean mix. Measurements of salinity along the coast help us understand the complex mixing between fresh and salty water and how this affects the local biology, physics, and chemistry of the seawater. However, the scope of our measurements is very small. Salinity data is collected by instruments on ships, moorings, and more recently underwater vehicles such as gliders. While these measurements are trusted to be very accurate, their spatial and temporal resolution leaves much to be desired when compared to say daily sea surface temperature estimated from a satellite in space.

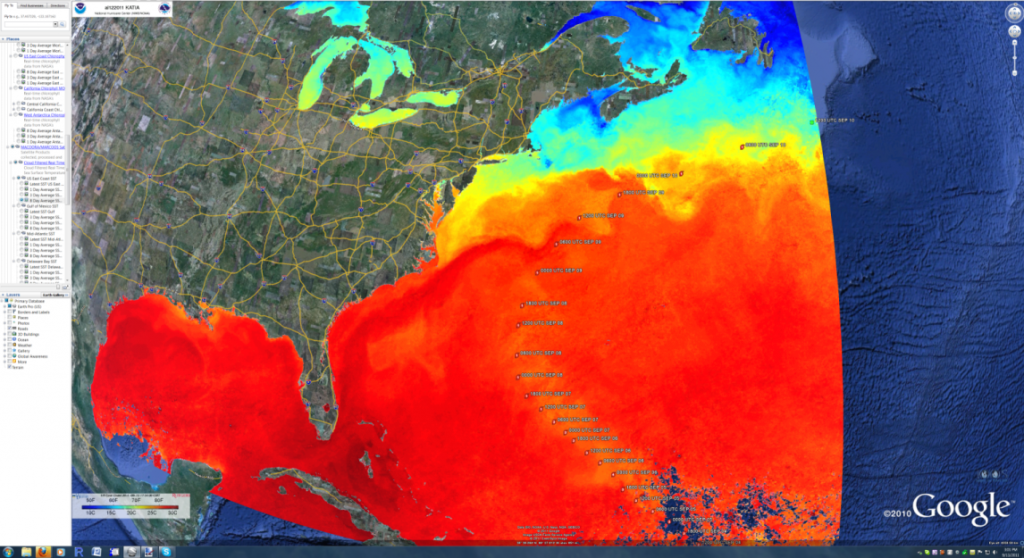

So, why can’t we just measure salinity from a satellite?Well, it’s not as simple, but it is possible. NASA’s Aquarius mission http://aquarius.nasa.gov/ which was launched this past August is taking advantage of a set of three advanced radiometers that are sensitive to salinity (1.413 GHz; L-band) and a scatterometer that corrects for the ocean’s surface roughness. With this they plan on measuring global salinity with a relative accuracy of 0.2 psu and a resolution of 150 km. This will provide a tremendous amount of insight on global ocean circulation, the water cycle, and climate change. This is great new for understanding global salinity changes. What about coastal salinity? What if I wanted to know the salinity in the Chesapeake Bay? That’s much smaller than 150 km.

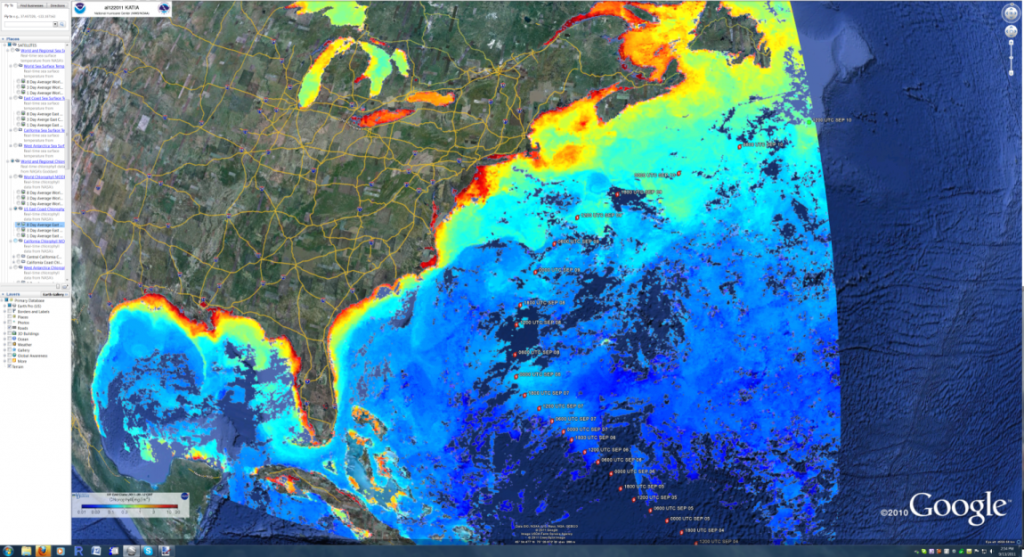

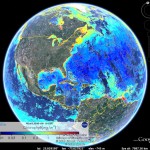

That’s where my project comes in. It involves NASA’s MODIS-Aqua satellite (conveniently already in orbit: http://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/), ocean color, and a basic understanding of the hydrography of the coastal Mid-Atlantic Ocean. Here’s how it works: we already know a few things about the color of the ocean, that is, the sunlight reflecting back from the ocean measured by the MODIS-Aqua satellite. We know enough that we can estimate the concentration of the photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll-a. So not only can we see temperature from space, but we can estimate chlorophyll-a concentrations too! Anyway, there are other things in the water that absorb light besides phytoplankton and alter the colors we measure from a satellite.

We group these other things into a category called colored dissolved organic material or CDOM. CDOM is non-living detritus in the water that either washes off from land or is generated biologically. It absorbs light in the ultraviolet and blue wavelengths, so it’s detectable from satellites. In coastal areas especially, its main source of production is runoff from land. So, CDOM originates from land and we can see a signal of it from satellites that measure color. What’s that have to do with salinity?

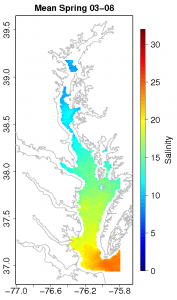

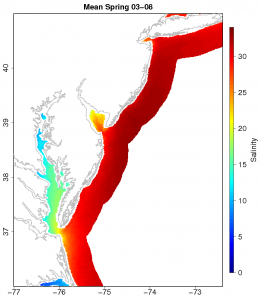

You may have already guessed it, but water from land is fresh. So, water in the coastal ocean that is high in CDOM should be fresher than surrounding low CDOM water. Now we have a basic understanding of the hydrography of the coastal Mid-Atlantic Ocean, how it relates to ocean color, and why we need the MODIS-Aqua satellite to measure it. So, I compiled a lot of salinity data from ships (over 2 million data points) in the Mid-Atlantic coastal region (Chesapeake, Delaware, and Hudson estuaries) and matched it with satellite data from the MODIS-Aqua satellite in space and time. Now I have a dataset that contains ocean color and salinity. Using a non-linear fitting technique, I produced an algorithm that can predict what the salinity of the water should be given a certain spectral reflectance. I made a few of these algorithms in the Mid-Atlantic, one specifically for the Chesapeake Bay. It has an error of ±1.72 psu and a resolution of 1 km. This isn’t too bad considering the range in salinity in the Chesapeake is from 0-35 psu, but of course there’s always room for improvement. Even so, this is an important first step for coastal remote sensing of salinity. An algorithm like this can be used to estimate salinity data on the same time and space scale as sea surface temperature. That’s pretty useful. The folks over at the NOAA coastwatch east coast node thought so too. They took my model for the Chesapeake Bay and are now producing experimental near-real time salinity images for the area. The images can be found here: http://coastwatch.chesapeakebay.noaa.gov/cb_salinity.html. They will test the algorithm to see if it is something they want to use

Climatologies of salinity for all of my models can be downloaded here: http://modata.ceoe.udel.edu/dev/egeiger/salinity_climatologies/.

I view this project as an overall support of the NASA Aquarius mission by providing high resolution coastal salinity estimates that are rooted in in situ observations. I hope this information proves to be useful for coastal ocean modeling and understanding the complex process that effect the important resource that is our coasts.